American Jews

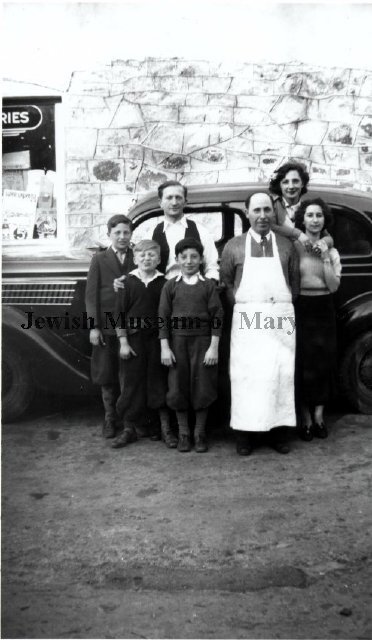

The Burke family outside the family grocery store, Baltimore, Maryland circa 1940.

During the 1930s, the majority of American Jews were immigrants themselves, having come to this country between 1881-1924. Their children were entering the mainstream but were not completely assimilated or accepted. They often experienced discrimination in employment, housing, and higher education.

The mood of the country was unwelcoming. Americans, focused on the severe economic problems caused by the Great Depression, were generally opposed to immigration and resisted involvement in overseas issues. Jews who sought to bring attention to Nazi crimes were often vilified publicly and castigated as warmongers, a chilling accusation in isolationist America.

American Jews found themselves in a tenuous position, forced to protect their own status at a time when their aid and support were needed in Europe. Some were intimidated; others worked individually or joined rescue and relief groups.

A small but unprecedented number of Jews held positions in the Roosevelt administration but, with few exceptions, they did not attempt to influence decisions related to the Jewish crisis.

There were many Jewish organizations that represented a broad spectrum of religious and secular viewpoints. In 1933, the American Jewish Congress, the B’nai Brith, Jewish War Veterans, and the American Jewish Commit- tee attempted to establish a boycott of German products, but it proved to be ineffective.

That same year, the American Jewish Congress, under the leadership of Rabbi Stephen Wise, organized a huge protest rally that attracted thousands at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

Although they were concerned and active, leaders of Jewish organizations were too often cautious about taking positions that might fan anti-Semitism or antagonize President Roosevelt.