In America 1933-45: Response to the Holocaust

Return to Full Exhibit

Who We Were

“The dove flew / Over all the world / And saw a lovely land / But the land was locked / And the key was broken.” - From a children’s rhyme printed in “Children of a Vanished World” by Roman Vishniac

Nazi Emigration Policy

From 1933-1939, the Nazis encouraged and often forced Jews to leave Germany and Austria, but routinely stripped them of their assets. Approximately 300,000 Jews fled. Under a transfer agreement with the Jewish agency, 50,000 were permitted to settle in Palestine.

In 1941, the Nazis effectively curtailed all Jewish emigration.

European Relatives

As the Nazi menace grew, many European Jews turned to relatives in the United States for help. Letters describing terrible hardships often ended with pleas for assistance in obtaining visas, a process that required relatives to furnish information about their income, a ten-year history of employment and signed affidavits pledging financial responsibility. Americans without adequate means often turned to friends or benefactors for help. Even when all requirements were met, visas were often summarily refused.

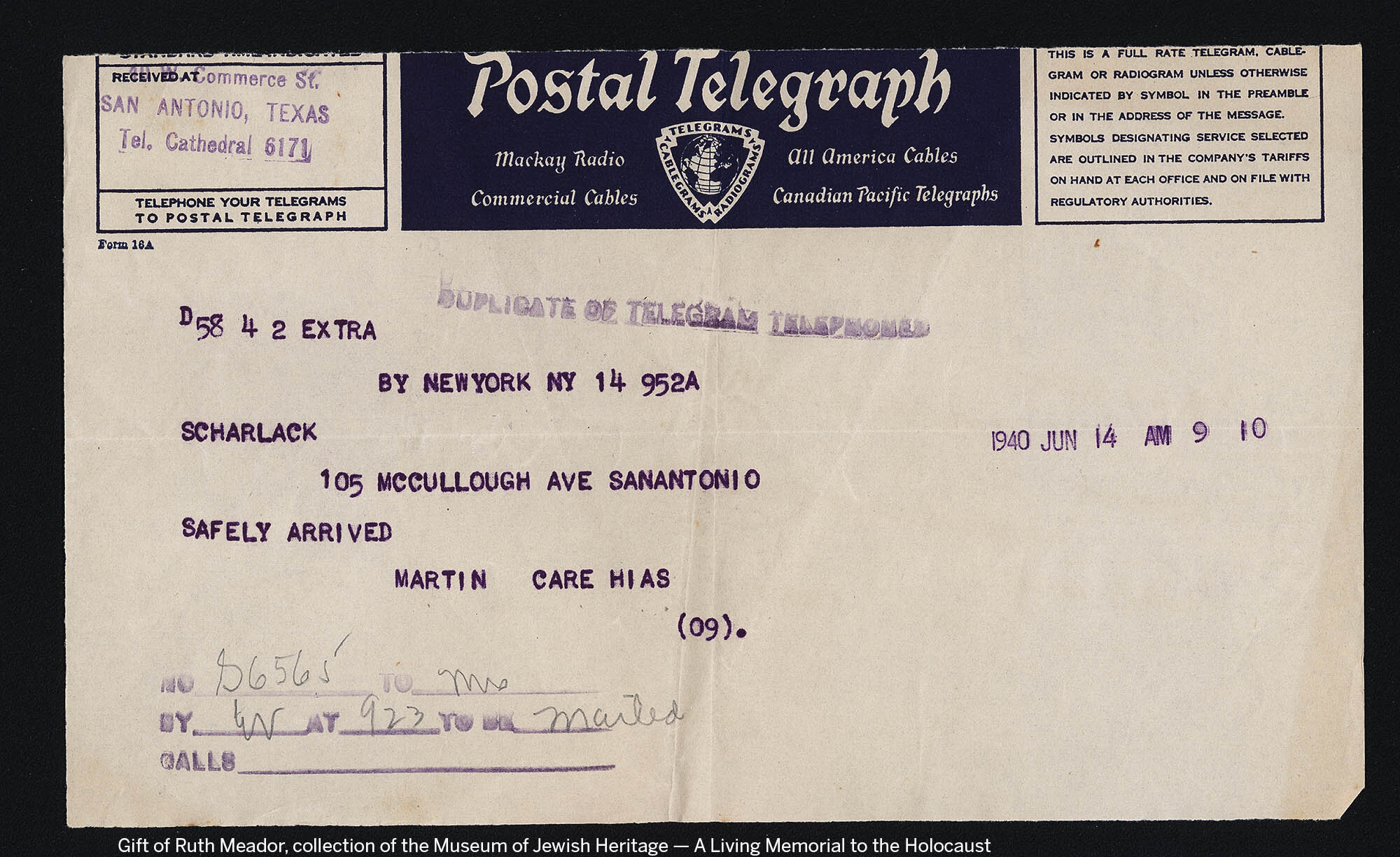

Telegram from Martin Amster to Blanka Scharlack: Safely Arrived

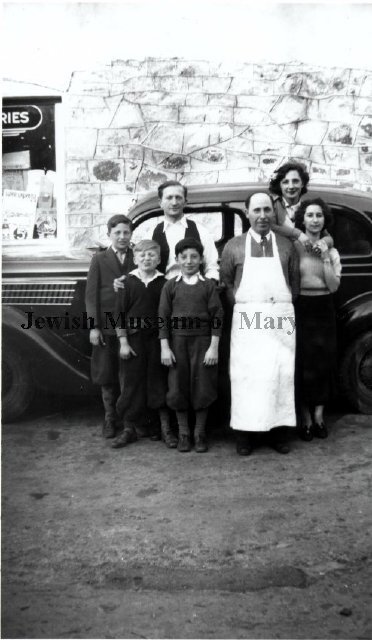

The Case of the Scharlack Family

Shortly after Hugo and Blanka Scharlack and their children came to San Antonio from Germany in 1938, they initiated efforts to bring their families to the United States. Over the next three years, they submitted the required affidavits, followed by a flood of letters to the State Department and other agencies pleading for approval of the visas applications. The Scharlacks enlisted the support of Rabbi Ephraim Frisch and Mayor Maury Maverick as well as family and friends who offered financial assistance. They met each visa requirement only to have American consulates in Germany demand additional information or summarily deny entry. Deposits were sent to cover the costs of transportation and every possible place of refuge was explored, but to no avail.

There were moments of hope in the Scharlacks’ daily crusade to save their families but mostly, there was anguish and despair. Correspondence from relatives in Germany ended abruptly in 1941.

What We Knew

The Press and the Public

“It has brought to them the final catastrophe, which threatens to leave them little except a nameless terror in their hearts. Beginning with the new year, all Jews find themselves destitute and without any chance of making a living . . . The only hope for most Jews in Germany lies in emigration. . .”

What Did We Know and When Did We Know It

Even before Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany in 1933, information about Nazi anti-Semitism appeared in the American press. The media gave broad coverage to the Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses, the Kristallnacht riots, and Cuba’s refusal to allow Jewish refugees on the S.S. St. Louis to disembark. After World War II began, less attention was focused on the fate of the Jews. Americans were consumed by the escalating conflict in Europe.

American Response to Kristallnacht

Americans protesting Kristallnacht

Thousands of Americans were outraged by Kristallnacht, the government-instigated riots against Jews in Nazi Germany and Austria in November 1938. President Franklin Roosevelt condemned the violence and extended temporary visas to 15,000 Germans who were already in the United States. Many were Jews. His action roused sharp criticism from immigration foes and anti-Semitic individuals and organizations who had already labeled Roosevelt’s New Deal “The Jew Deal.”

Six days after Kristallnacht, 500 Harvard and Radcliffe students staged a protest rally that led to the formation of the Harvard Committee to Aid German Student Refugees. With endorsements from the presidents of both schools, the group launched a fund drive to pay for living expenses for matriculating European students. Fourteen young refugees from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia were enrolled at Harvard and two more were admitted to Radcliffe College. The initiative generated national publicity and spread quickly to other campuses. Their efforts, however, were thwarted by immigration restrictions that limited the number of students permitted to enter the country.

Following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, information about mass kill- ings and atrocities filtered into American news agencies but was given minimal attention. Reports were often relegated to the inner pages of newspapers or folded into general accounts of the war. Some periodicals, most notably The Nation and The New Republic, ran articles about the persecution of the Jews, as did some Catholic and Protestant publications.

The Jewish Telegraphic Agency provided accurate coverage about Nazi atrocities to Jewish community newspapers. In San Antonio, information appeared in The Jewish Press, published by Jacob Riklin, and The Jewish Record.